Operating Leverage as a Source of Market Inefficiency

One source of market inefficiency is margins. Specifically, projecting future margin profiles in cases of extreme operating leverage.

Pat Dorsey, in this talk at Google, explains:

PAT DORSEY: “So when Morningstar initiated on MasterCard, when it went public at $40, $50 a share, I remember our analyst wanted to put like a $100, $110 price target on it. And I was like, dude, you’re nuts, man. This thing is coming public at like $40. We’re not going to stick our necks out that far. Come on. How good a business is this?

And what he did is he just walked through fixed versus variable. That basically, okay — [there’s] very little variable costs in this business. You’ve got the fixed cost of a network, the data processing network. But then of the incremental revenue, tons will flow down to the bottom line. And this is where — and this is a geek thing — when you’re modeling out a high-growth company, don’t model in percentages. Model in dollars.

So it optically looks weird to say, margins are going to go from 13% to 25%. Ah! This is huge! My God, that’s never going to happen! So don’t do it in percentages. Don’t do operating margins doing from x to y. Think about fixed versus variable. How many dollars will they need to spend to get each dollar of additional revenue? And then see what operating margin falls out of that. And you may come to a very different conclusion.”

AUDIENCE: “Is that like operating leverage that you--”

PAT DORSEY: “Yeah, it’s operating leverage. And I have found that operating leverage is frequently one of the most mispriced things in the market because nobody wants to like hand their boss the portfolio manager or the director of research a model that shows something going from 13% to 30% margins. Because they’re going to get it back, and they’re going to say, you’re nuts, man.”

I’ve found this to be very true.

Yes, these high-growth/high-leverage models are more common today than twenty years ago. But still — banking on substantial margin inflection is scary because (1) it rarely happens (especially outside of tech), (2) even if it does happen, timing can be hard to predict and (3) you are sticking your neck out, as Dorsey says, by underwriting to it (much better to underwrite to strong-but-not-crazy operating leverage — you can still get credit for a nice call, but don’t have to look stupid if/when extreme operating leverage ultimately fails to materialize).

I’d say there’s a natural cap on believable margin expansion over a ~5 year window that lies somewhere in the neighborhood of ~1,000 bps (and this would be in an upside scenario, almost certainly not a base case).

So what actually happened at MasterCard? I was curious, so I went back and looked.

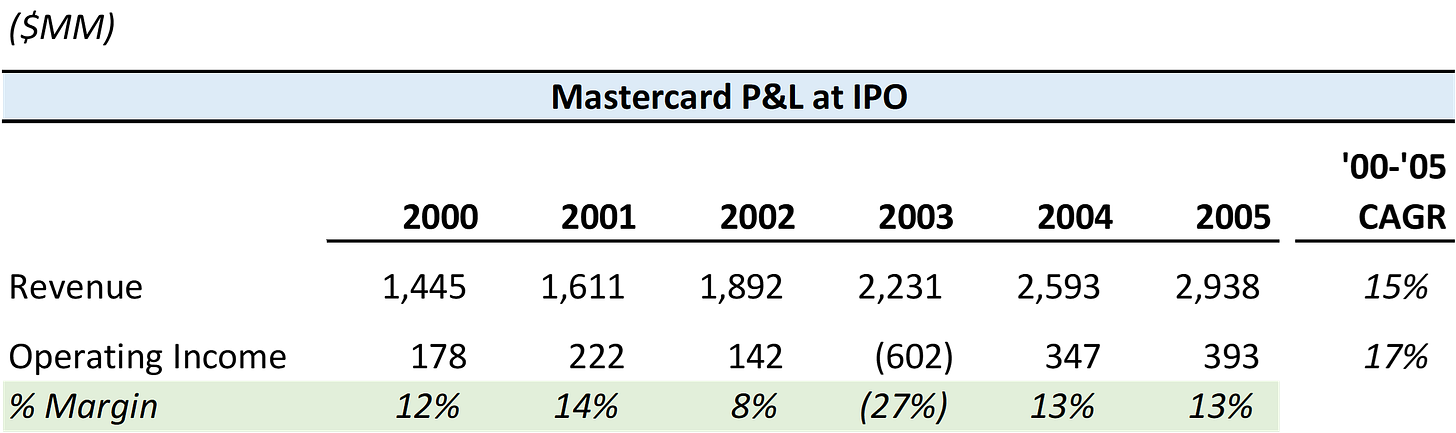

Here is the P&L you would have seen at the time of its IPO in 2006:

As we can see, MasterCard demonstrated healthy growth (a 15% 5-yr revenue CAGR) combined with a consistent margin profile of 12-14%.

Looking at this, a responsible analyst taking a cursory look might have baked in something like ~0-500 bps of margin improvement over the next ~five years (in a base case scenario). A better analyst, taking the time to really understand MasterCard’s unit economics/incremental margin profile, might’ve still only forecasted say ~500-1,000 bps of incremental improvement.

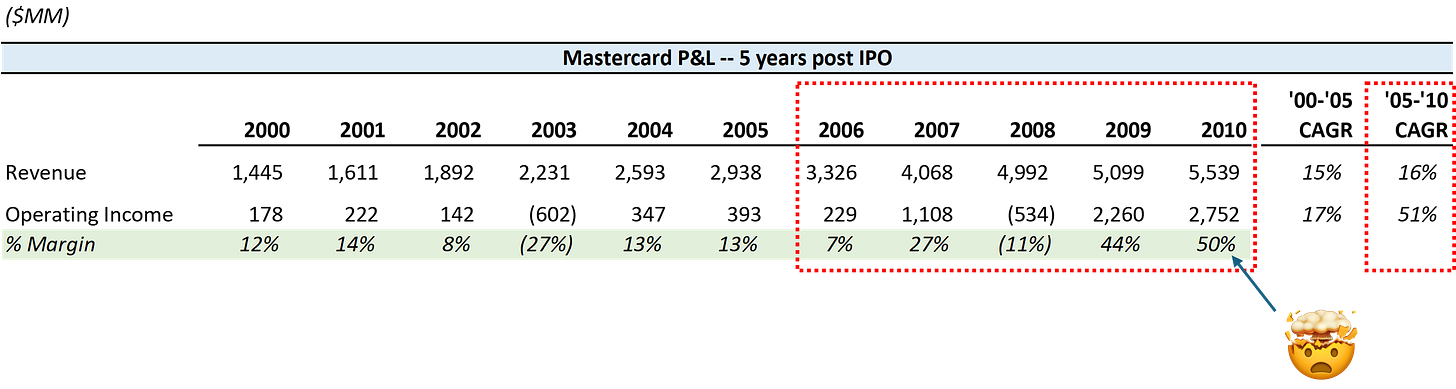

Here’s what actually happened:

Quite amazingly, MasterCard added almost zero additional expense from 2005 to 2010 ($2.5bn vs. $2.8bn). In the meantime, revenue grew by $2.6bn. As a result, Mastercard generated in operating income in 2010 ($2.8bn) almost as much as it generated in revenue in 2005 ($2.9bn).

While I’d bet many analysts at the time of MasterCard’s IPO might have correctly forecasted its 5-year forward revenue CAGR within a tight-ish band, there’s no way anybody would have done the same on margins. Even the Morningstar analyst that Dorsey thought was “nuts” was likely way short of the mark. The figures are hard for me to believe, even staring at them today.

But I think the point is, though, that no one is really to blame. Margin expansion like this rarely happens, so you shouldn’t expect it. Further, even if you did expect it, sticking your neck out too far, as Dorsey says, entails career/reputational risk that is scary and unnecessary.

So for the discerning analyst, situations may persist where high-leverage businesses are priced for strong-but-not-dramatic operating leverage, but where fat tail probabilities exist for the latter.

Excellent article Ryan. Thanks for publishing